March 24 to April 18,1945

At 4:25 AM on the morning of 24 March the four rifle companies of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada (Lt.-Col. P. W. Strickland) began crossing the Rhine in Buffaloes under “sporadic shelling”. The H.L.I., fighting in this phase under the154th Brigade, was the first Canadian unit across. On the farther bank, guides led it to an assembly area north-west of Rees. The 154th Brigade, we have seen, had met stiff resistance at Speldrop (the Highland Division’s commander, General Rennie, was killed in the brigade area during the morning) and the Canadians were ordered to capture the village. Some parties of the Black Watch were still cut off and surrounded in Speldrop when, in the late afternoon, the Highland Light Infantry advanced against the outskirts. The defending paratroops fought fiercely, but the assault was pressed with determination over open ground, valuable supporting fire being provided by six field and two medium regiments and two 7.2-inch batteries. Within the village the enemy held out desperately in fortified houses, which could only be reduced by “Wasp” flame-throwers and concentrations of artillery fire. The battle continued well on into the morning [of the 25th]. Houses had to be cleared at the point of the bayonet and single Germans made suicidal attempts to break up our attacks… It was necessary to push right through the town and drive the enemy out into fields where they could be dealt with.

The H.L.I. relieved the trapped detachments of the Black Watch and put out the last embers of resistance. Their casualties during the two days’ fighting were, for the circumstances, light: 33, including ten killed.

Meanwhile, on the afternoon of the 24th, the remainder of the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade had joined their comrades east of the Rhine. The Highland Light Infantry of Canada came back under Brigadier Rockingham and that night his brigade, reinforced by the North Shore Regiment from the 8th, relieved the 154th. During the next two days the 9th Brigade struggled to open an exit from the pocket formed by the Alter Rhein northwest of Rees. These operations centred about the villages of Grietherbusch, Bienen and Millingen. While they were in progress, on the afternoon of the 25th, the brigade came under the command of the 43rd (Wessex) Division which was moving into the bridgehead. General Horrocks was thus gradually implementing his plan to develop the attack on a three-division front, with the 51st, 43rd and 3rd Canadian Divisions right, centre and left respectively.

On the left of the whole Allied advance, The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders captured Grietherbusch without too much difficulty; but far heavier opposition was encountered at Bienen. There, on the 25th, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders attacked across open ground against very determined defenders. The Canadians had, in fact, drawn in the lottery the area on the British front where resistance was fiercest. The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had been put in here from Army Group Reserve to hold the Alter Rhein bottleneck and the important road junction of Bienen. Although artillery and medium machine-guns of The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa (M.G.) lent support, the North Nova Scotias were soon pinned down by German automatic weapons and mortars. “The battalion had quite definitely lost the initiative and contact between platoons was next to impossible because of the murderous fire and heavy mortaring.” Early in the afternoon General Horrocks visited the Canadian sector while, with the help of armour and Wasps, Lt.-Col. Forbes mounted a new attack against the village. By the end of the day his men had penetrated the southern portion; but their casualties had been very severe-114, of which 43 were fatal. As the North Nova Scotias’ diarist wrote, it had been “a long, hard, bitter fight against excellent troops who were determined to fight to the end”. Helped by a troop of 17-pounder self-propelled guns of the 3rd Anti-Tank Regiment R.C.A., The Highland Light Infantry of Canada now took over the task of clearing the rest of Bienen. “Progress was very slow as the enemy fought like madmen.” But the H.L.I. were not to be discouraged, and during the morning of the 26th they mopped up the last resistance in the place.

About a mile north-east of Bienen was Millingen, on the main railway line between Emmerich and Wesel. This village now became the target of The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment. It went in at noon on the 26th, with the support of artillery and armour, and was completely successful, all objectives being secured on the same afternoon; but the day cost the life of its commander, Lt.-Col. J. W. H. Rowley, who was killed by a shell early in the attack.

Simultaneously the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders cleared the villages to the west of Millingen. The Canadian buildup east of the Rhine continued with the arrival of the 1st Battalion, The Canadian Scottish Regiment, also under the command of the 9th Brigade. As the bridgehead was steadily enlarged the remainder of the 3rd Division prepared to follow; on the 27th General Keefler established his tactical headquarters on the right bank while the balance of the 7th Brigade joined the 9th in the bridgehead; and at 5:00 PM he took over the left sector of the 30th Corps line. His last brigade, the 8th, crossed the river on 28 March. At noon that day the 2nd Canadian Corps took the 3rd Canadian Division, and its sector of the bridgehead, under command.

At the end of March careful consideration was also being given to the problem of an assault crossing of the River Ijssel from east to west-the task assigned to First Canadian Army in Montgomery’s earlier directive. The object, we have seen, was to open a route through Arnhem and Zutphen to maintain forces east of the Rhine and the Ijssel. Although there was little likelihood that the enemy could offer effective opposition along the Ijssel, the river was itself a considerable obstacle, varying in width from 350 to 600 feet with high floodbanks.

Meanwhile preparations for the northern drive continued. General Simonds established his command post near Bienen, where he could direct the 3rd Division during its advance on Emmerich while maintaining contact with the 30th Corps on his right flank. The 2nd Canadian Division, which had been resting in the Reichswald, crossed the Rhine on 28-29 March, led by the 6th Brigade, now commanded by Brigadier J. V. Allard. It was to become the spearhead of the 2nd Corps’ northern advance (Operation “HAYMAKER”), with the 3rd and 4th Canadian Divisions on its left and right respectively. At the end of the month the 4th Armoured Division joined the force in the bridgehead, the divisional staff being reminded of “the crowded sites of Normandy”.

Before General Crerar could take control of Canadian operations east of the Rhine it was essential to open a maintenance route across the river at Emmerich. This depended, in turn, on the progress of operations to capture the city and the nearby Hoch Elten ridge. This important job fell to the 3rd Canadian Division. On the night of March 27-28th, Brigadier T. G. Gibson’s 7th Infantry Brigade opened the attack on the eastern approaches to Emmerich. The Canadian Scottish quickly captured the village of Vrasselt and pressed on during the night; The Regina Rifle Regiment occupied Dornick the following morning. The units reached the city’s outskirts before they met serious opposition, from units of the 6th Parachute and the 346th Infantry Divisions. General Keefler then ordered the 7th Brigade to continue its attacks to clear Emmerich and a wooded area north of the city while he 8th Brigade prepared to pass through and attack the Hoch Elten feature. These operations were supported by tanks of the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment) and “Crocodiles” of “C” Squadron, The Fife and Forfar Yeomanry.

During the night of March 28-29th, the Canadian Scottish experienced what they described as “probably the most vicious fighting of the war during the battle for Emmerich” in attempting to expand their bridgehead over the Landwehr Canal. A company of the Regina Rifles assisted in this difficult task and the stubborn enemy was gradually driven back into the city, while our engineers bridged the canal during the darkness. The way was then clear for concerted thrusts into the heart of the built-up area.

Emmerich, which had a normal population of about 16,000, had been heavily bombed and was “completely devastated except for one street along which a few buildings were more or less intact” (When the 1st Canadian Division passed through Emmerich nine days later it recorded that “only Cassino in Italy looks worse”.) On the morning of the 29th the Reginas, supported by tanks and Crocodiles, launched an attack to clear the southern portion of the city. Resistance stiffened as the operation progressed. “Enemy defences consisted mainly of fortified houses and tanks and as each house and building had to be searched progress was slow.” When the troops forced their way into the central area of the city they faced a problem familiar from Normandy and the Channel Ports: “our tanks in support found it almost impossible to manoeuvre due to well-sited road blocks and rubble”. While the Reginas cleared the southern part of Emmerich, The Royal Winnipeg Rifles fought steadily through the northern section, beating back a fierce German counter-attack early on the 30th. On that day the Canadian Scottish again became the division’s vanguard, capturing a large cement works on the western outskirts of the city as a start line for the 8th Brigade’s operation. The 7th Brigade completed its task on the following morning. During the previous three days its infantry battalions had suffered 172 casualties, including 44 killed or died of wounds; the heaviest loss fell on the Canadian Scottish.

The 8th Brigade was now to carry forward the attack and capture the Hoch Elten “feature”. We have already noted the tactical importance of this high wooded ridge some three miles north-west of Emmerich. It dominated our engineers’ Rhine bridging sites and German possession of it might thereby delay the full participation of First Canadian Army in the battle. For this reason the Hoch Elten area had been subjected to particularly severe artillery and air bombardment during the days preceding the attack. These measures had the effect of easing the task of the 8th Brigade when it advanced on the night of 30-31 March. The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada and Le Régiment de la Chaudière led the way; the latter, with no doubt some pardonable exaggeration, describes the ground as “peut-etre le plus bombarde dans l’histoire de la guerre” The enemy’s surviving artillery and mortars fired on the axes of advance but, in general, there was little opposition. On the following night the Chaudière entered the village of Elten, west of the ridge, while the Queen’s Own and the North Shore completed the occupation of the wooded area. Meanwhile, on the 3rd Division’s inland flank, the 9th Brigade had cleared the woods north of Emmerich and the nearby town of ’s-Heerenberg. Elimination of the Germans’ hold on Hoch Elten enabled the engineers to begin construction of a low-level Bailey pontoon bridge–a “Class 40” bridge capable of carrying tanks–across the Rhine at Emmerich. At noon on 31 March the 2nd Canadian Army Troops Engineers began work. They were assisted by various elements of British and Canadian services and a squadron of landing craft from Naval Force “U”. Although the enemy could not interfere actively with the bridging operation, his minefields on the northern bank (the Rhine flows due west at Emmerich) had to be cleared, and a west wind impeded the manoeuvring of floating bays into position. Nevertheless, “Melville” Bridge, as it was named, in honour of Brigadier J. L. Melville, a former Chief Engineer of First Canadian Army, was opened to traffic at 8:00 p.m. the following day. Its length was 1373 feet, and from the moment it was opened “traffic went over it nose to tail night and day”. Completion of two other bridges at Emmerich soon followed. One was a secondary (Class 15) bridge. The other, named for Brigadier A. T. MacLean, also a former Chief Engineer, was a high-level Bailey pontoon bridge (Class 40) which was built by the 1st Canadian Army Troops Engineers. It was given extended landing ramps in anticipation of further flooding. Thus the way was clear for General Crerar to take control of Canadian operations east of the Rhine.

The 2nd Corps’ northern advance had already gathered momentum. After concentrating in the Bienen-Millingen area, the 2nd Division moved forward on the 3rd Division’s right, recrossing the Dutch-German frontier and clearing Netterden on 30 March. In general, “scattered clusters” of opposition were reported, with only token resistance in certain sectors. While the 3rd Division was capturing the Hoch Elten feature, General Matthews’ troops thrust forward to Etten, seven miles north-east of Emmerich, with the Wessex Division temporarily on their right flank. The 4th Canadian Armoured Division moved in here on 1 April. General Vokes’ immediate task was to occupy the Lochem-Ruurlo area and then press on across the Twente Canal to Delden and Borne.

As our formations fanned out east of the Ijssel-Rhine junction, German disorganization facilitated rapid advance. It soon became apparent that apart from Zutphen, which was well protected by water lines connected with the Ijssel, the enemy’s next natural defence line would be the Twente Canal. This ran eastward from the Ijssel north of Zutphen, past Lochem and through the southern outskirts of Hengelo to Enschede, roughly at right angles to the axes of the 2nd Corps. Defending the main portion of the Canal as far east as Hengelo was our old antagonist the 6th Parachute Division. East of the Rhine the division had been reinforced by replacement and training units, together with the 31st Reserve Parachute Regiment; the latter consisted of three battalions, one of which was an artillery unit armed with ordnance of various calibres. On the eve of the Canadian attack Plocher was also reinforced by a “Police Regiment” of doubtful quality.

Pressing forward through Doetinchem and Vorden, the 2nd Canadian Division was first to cross the Twente Canal. On the night of April 2-3rd the 4th Infantry Brigade made the assault near Almen, four miles east of Zutphen. The speed of the attack, following a rapid 20-mile advance, caught the enemy napping. Although the Germans had blown the bridges over the Canal, their defences were still disorganized.

When the Royal Regiment of Canada crossed in assault boats, their first prisoners were mainly engineers, busy preparing positions for infantry who arrived too late to oppose the crossing. Our own engineers quickly began work on a ferry, while a company of The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry reinforced the bridgehead. About midnight the enemy reacted vigorously, beginning “a most intense mortaring and shelling of the proposed ferry site” and temporarily stopping the engineers’ work. Nevertheless, they soon had rafts operating across the Canal and, during the next day, these carried armoured cars of the 8th Reconnaissance Regiment (14th Canadian Hussars), self-propelled guns of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment R.C.A., and tanks of the 10th Armoured Regiment (The Fort Garry Horse) to the infantry’s support. The Germans mistakenly believed that the Canadians used amphibious tanks. Although the enemy launched spasmodic counterattacks, and continued to interfere with bridging and rafting, the bridgehead was consolidated and expanded on 3 April. At the end of the day The Essex Scottish Regiment was preparing to join the remainder of the brigade north of the Canal and the way was clear for the 5th Brigade to continue the northern drive. The 4th Brigade’s losses had been comparatively light. Meanwhile, the 6th Brigade had eliminated resistance on the left flank, closer to the Ijssel River.

The casualties inflicted on the Wehrmacht in earlier battles were obviously having a significant effect. The 4th Brigade noted, the enemy tactics appear almost juvenile at times–he is doing everything the book says as usual, but his training here shows that the calibre of troops opposing us is not what it used to be. Each enemy attack suffered very heavy casualties and usually a number of PW [were] taken-grubby, dirty, slender youths, boys and old men.

Although further German resistance was rapidly becoming meaningless, fierce struggles would continue in isolated sectors until the disintegration was complete.

Just west of Delden, 20 miles east of the 2nd Division’s crossing, the 4th Armoured Division carved out a second bridgehead across the Twente. On 2 April General Vokes’ tanks and motorized infantry had reached the canal at Lochem, relieving a formation of the Wessex Division, but found no suitable crossing site. The enemy held the far bank in some strength, inflicting casualties on our troops. Then, on the evening of the 3rd, Lt.-Col. R. C. Coleman’s Lincoln and Welland Regiment (fighting under the 4th Armoured Brigade) threw two companies across the canal and a company of The Lake Superior Regiment (Motor) made a diversionary attack against lock-gates about 1000 yards west of the main crossing. After indulging in “scattered sniping and small arms fire” throughout the day, the enemy was able to direct only “moderate machine-gun and mortar fire” against the assault. Counter-attacks were beaten off by our infantry with the help of the divisional artillery and the bridgehead was secured. Again the pressing problem was one of bridging: it was essential to construct quickly a bridge that would carry the heavy vehicles of the 4th Armoured Brigade. Fortunately, the Lake Superior Regiment discovered at the lock-gates a 30-foot gap which could be bridged. Initially there had been no intention of bridging there, but. now the 9th Field Squadron R.C.E. was sent in and in two hours and a quarter the bridge was built, and the brigade began to roll across. The brunt of the operations on 3-4 April fell on The Lincoln and Welland Regiment, which suffered 67 casualties.

April 1-10- April1- South Saskatchewan Regt. suffers 18 casualties including 3 killed at Etten. On same day Canadian Black Watch 5th CIB to lead attack on Doetinchem then pass to the Calgary Highlanders who faced a tenacious battle in the main square with snipers, machine guns and mortars. Fort Garry Horse tanks in support. Calgary casualties were 41 including 9 killed.

2nd Div. pressing through Doetinchem, meet with large elements of 1st Canadian Army at Laag-Keppel then advance through Hengelo, Vorden to cross the Twente over a large bridge near Almen. Bridge is blown just as they arrive, so a Bailey Bridge is built.(Still there and part of our tour) Twente canal is well defended by 6th Parachute Div. Lochem was rear echelon HQ for 300 paratroopers of this Div. Capt. George Blackburn earned his MC in these battles, as a FOO with the 4th Field Regiment assigned to the Royal Canadian Regiment, of 4th CIB. Blackburn travelled with the famous 8th Recce Regt. (14th Canadian Hussars). He was observing from the 2nd floor of a building known as Villa Rozenhof. This building has been restored as a B& B and is an integral feature of our tour. Capt. Blackburn visited the area in 2004 and showed the owners the window he observed from. The owners of Villa Rozenhof will allow guests to look through this window and survey the field as Capt. Blackburn did.

On April 1 & 2, the Regina Rifles of 7th CIB, supported by the 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers approach Wehl. Intense short battle and 4 Canadians killed.

April 4-5- An intense battle raged for 2 days in Leesten which resulted in 30 casualties including 11 dead, for the Glens (Stormont Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders)

At the same time, a battle in Laren and surrounding area, raged on against the Paratroopers resulting in many casualties, including civilians. The story of Laren and its fierce Dutch Resistance to the dreaded NSB is a fascinating and sad one. The casualty (dead only) list for this small town is as follows;

| Dutch Army | 1 |

| Resistance members executed | 2 |

| Executed by the Resistance | 3 |

| Dutch in concentration camps | 7 |

| Local civilians | 14 |

| Airplane crashes | 3 Australians, 4 Germans, 2 Brits |

| Canadian soldiers | 31 Total, including; |

| – 8th Recce | 3 |

| – Black Watch | 13 |

| – Fort Garry Horse | 1 |

| – Regt. de Maissoneuve | 8 |

| – Toronto Scottish | 1 |

| – Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal | 5 |

| German Soldiers | 40 (Est.) |

April 4-7- Because of fanatical resistance from 361st Infantry Div. and 3rd Para. it becomes necessary to commit the entire 3rd CDN Div. to liberate Zutphen. Participants included Regina Rifles, Royal Winnipeg Rifles, 17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars, Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry Highlanders, Highland Light Infantry, North Nova Scotia Highlanders, North Shore Regiment (had 20 killed here), Regiment de la Chaudiere & Sherbrooke Fusiliers.

April 8-10- Battle for Deventer with Regina Rifles, Winnipeg Rifles, Canadian Scottish, Sherbrooke Fusiliers and British Crocodile (Flamethrower) Troop. 8 Canadians Killed. Canadians received great support from the Dutch resistance.

When the 2nd Division lunged forward from the Twente available intelligence indicated that there could not be more than three German divisions in the northern and eastern Netherlands. Headquarters 21st Army Group did not favour trapping these formations in the western portion of the country since this would side-track Allied forces needed elsewhere. Rather, the intention was to press the enemy north and east of his Ijssel defences, forcing him to escape from the northern end of the “bag”,

On 6 April the 6th Infantry Brigade reached the Schipbeek Canal about eight miles east of Deventer. The enemy had blown the only bridge in the area, but The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada found that marching troops could still cross on the damaged structure and against light opposition they soon established a bridgehead on the northern bank. The following day the 2nd Division drove on in the direction of Holten. The divisional staff noted that the supporting R.A.F. were “howling for targets” but that “with this fast-moving advance, enemy headquarters, gun positions and installations are almost impossible to pinpoint”.

Zutphen and Deventer

While General Simonds’ centre and right flank were making rapid progress north of the Twente Canal the 3rd Canadian Division, on his left sector, was preparing to capture Zutphen and Deventer. Advancing steadily northward from the Hoch Elten area, it had cleared the right bank of the Ijssel, meeting light opposition at Wehl on 2 April. Since, at this time, the flanking 2nd Division was in the lead, Simonds instructed that formation to “tap out and, if opposition not heavy, capture Zutphen”. But the enemy’s evident intention to hold the town, and the 2nd Division’s rapid progress north of the Twente Canal, soon made it necessary for the 3rd Division to take on Zutphen. While the 8th Infantry Brigade contained Doesburg, and the 7th cleared the western end of the Twente on 5 April, the 9th Brigade closed in on the southern and eastern approaches to Zutphen. This sector was defended by the 361st Infantry Division of the 88th Corps, with a parachute training battalion under command. These troops, many of them “teen-aged youngsters”, fought very fiercely. The 9th Brigade encountered stiff resistance at Baronsbergen and Warnsveld, on the outskirts of the town, which was covered by old water defences connected with the Ijssel. To pass one drainage ditch the pioneer platoon of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada built a bridge “with 4.2″ mortar boxes, reinforced with timber and ballast”–and it proved strong enough to carry the supporting tanks of “A” Squadron of the 27th Armoured Regiment (The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment).

Having secured the approaches to the town, the 9th Brigade was withdrawn on 7 April to add momentum to the drive north of the Twente and the 8th continued the operations to reduce Zutphen. It had launched its attack on the 6th, developing a two-pronged thrust into the town from the east with the North Shore Regiment on the right and Le Régiment de la Chaudière on the left. The North Shore ran into heavy opposition, with hand-to-hand fighting, but the Chaudière were able to make good progress. Accordingly, the plan was changed, the North Shore being withdrawn to pass through the right flank of the Chaudière. Fighting continued on the 7th. Sometimes our infantry was pinned down by snipers and machine-gun fire. Nevertheless, as in the operations on the Twente Canal, “for the first time there was evidence that the enemy’s attitude was gradually changing and although he fought well at times, the old tenacity was lacking”. The coup de grâce was given on the morning of the 8th, when the brigade penetrated the factory area with the help of Crocodiles. By midday the historic old town had been completely cleared, some of the defenders escaping across the Ijssel in rubber boats.

As the 8th Brigade was completing its work at Zutphen, the 9th was establishing a bridgehead across the Schipbeek Canal, some five miles north of the Twente, and the 7th was preparing to assault Deventer. The capture of this town was an essential preliminary to General Simonds’ attack across the Ijssel in conjunction with General Foulkes’ operations at Arnhem.

Deventer, like Zutphen, lay on the right bank of the Ijssel with its approaches well protected by a maze of waterways. Again, it was necessary to attack from the east. After “a very hard struggle” the 7th Brigade crossed the Zijkanaal, running north-east from the town’s outskirts, on the evening of April 9th. The Canadian Scottish led the way, capturing the nearby village of Schalkhaar without difficulty. When three German tanks appeared on the morning of the 10th one was quickly destroyed, and the others put to flight by “B” Squadron of the 27th Armoured Regiment. At midday Brigadier Gibson’s main attack began, with the Canadian Scottish and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles right and left, respectively, and The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, temporarily under command, maintaining pressure against the town’s south-eastern approaches. The enemy was forced back to his last major defensive line-an anti-tank ditch surrounding the town–but this did not long delay our troops. Resistance crumbled as many Germans were captured and others attempted to escape across the Ijssel, a manoeuvre rendered hazardous by the cooperating artillery of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division. By the evening of the 10th the brigade had occupied the main part of Deventer and, during the night, The Regina Rifle Regiment passed through the Winnipegs, clearing the south-eastern suburbs. Twenty-four hours after the main attack began Deventer was entirely in our hands, much of the credit for the speedy clearing of the town being due to “the extremely-well-organized Dutch Underground”. The 7th Brigade’s total infantry casualties (including those of the Queen’s Own) were 126; the brigade reported capturing about 500 prisoners.

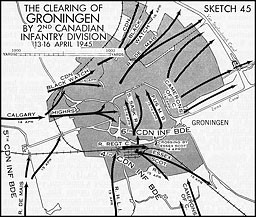

The climax to these operations occurred at Groningen. On the evening of April 13th, the 4th Brigade penetrated the city’s south-western outskirts; but miscellaneous German units, aided by Dutch S.S. troops, resisted strenuously. “The fighting continued on into the night, fierce hand-to-hand encounters-with our men having to clear every room of four-story apartments, and even then, the snipers would come back again because our troops could not occupy so much space.” A characteristic of the defence was the siting of machine-guns in basements. SS troops were discovered sniping in civilian clothes, and orders were issued for these men to be shot on sight. On the evening of April 14th, the Essex Scottish found a bridge intact across a large canal in the southern portion of the city; “A” Company sped across it in “Kangaroos” and seized houses that dominated it. The 6th Brigade then passed through; simultaneously, the 5th moved into Groningen from the west. “In spite of the severe fighting… great crowds of civilians thronged the streets-apparently more excited than frightened by the sound of nearby rifle and machine-gun fire.” Out of regard for these civilians, the Canadians did not bomb or shell the city, thereby accepting the possibility of delay and additional casualties.

The German commander and his staff surrendered on the 16th, but stubborn remnants of the garrison held out a little longer.

April 13-16, 1945

Try watching this video on https://youtube.com.

Maps

Liberation of Holland – Left Flank